This page is designed to support health and care professionals in promoting the importance of vaccinations across our diverse communities in south east London. You can also signpost people to our public website page on children’s immunisations.

Jump to promotional resources

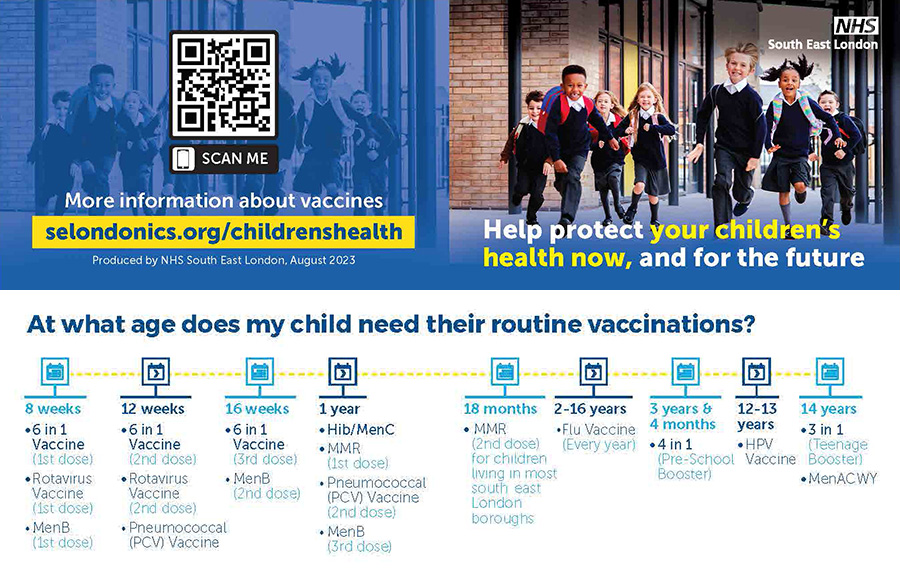

Vaccines and when children should have them

Our interactive online timeline shows when children are due their routine vaccinations.

The MMR vaccine

Updated: May 2024

Numbers of measles cases are rising in London and across the country. The MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps and rubella, has one of the lowest take up rates of all childhood immunisations.

Key information on MMR messages to give to parents and use on your websites and other channels:

- If your child has missed any of their MMR vaccinations, it’s never too late to catch up – check your child’s red book. If you don’t have a red book, contact your GP practice to find out if they are fully vaccinated.

- The MMR vaccine is safe and effective. It protects against three serious illnesses – measles, mumps and rubella. These are highly infectious conditions that can easily spread between unvaccinated people.

- The MMR vaccine is given in two doses – the first at one year old and the second at 18 months old in south east London. Two doses are needed for lifelong protection.

Jump to FAQs to support parent/carer conversations on MMR

The whooping cough (pertussis) vaccine

Updated: May 2024

Whooping cough (pertussis) cases continue to rise, with 1,319 cases confirmed nationally in March 2024 compared with 858 cases for the whole of 2023. There have also sadly been 5 reported deaths in infants who developed pertussis in the first quarter of 2024 – in each of these cases the mother had not received the pertussis vaccine.

Please do continue to encourage uptake of the pertussis vaccine which is offered to women from 16 weeks of their pregnancy. It is then offered again to babies when they’re 8, 12 and 16 weeks old in the 6-in-1 vaccine.

Guidance for healthcare professionals on the public health management of pertussis (whooping cough) can be found on the gov.uk website.

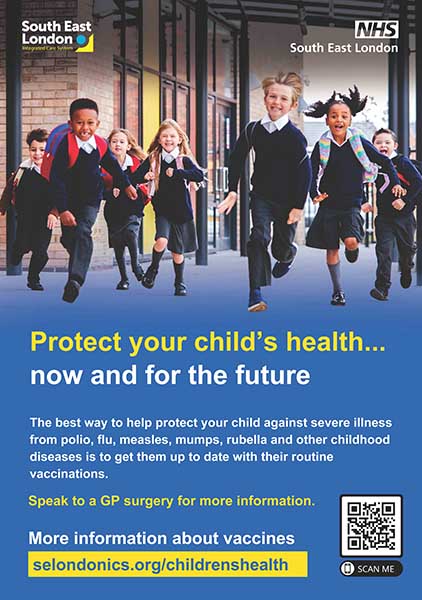

Resources: promotional materials

We have produced various resources to help raise awareness of the importance of children’s immunisations.

You can download and print these locally.